From Language to Writing: The Dawn of History

The development of alphabet based language systems in general, a development that occurs in the Mediterranean at around the end of the second millennium BCE or so, represents a major evolution in the history of mankind. It’s invention, if we may call it that, reflects the need for a system of writing that a) meets the need to document various languages that existed at the time in a single form of writing, i.e. a phonetic description of words rather than a symbolic representation of meaning, b) the need for a writing system that could be more easily learned, transcribed and understood by a broader base of intellectuals and scribes.

This invention had an interesting byproduct however, one which was perhaps not originally intended when it was invented, it allowed for the development and systemization of much more precise, complex and abstract intellectual systems of thought than was possible in the older, more archaic forms of writing which were more symbolic, had little or no grammatical structure, and were generally less specific in terms of meaning. This allowed for a much more accurate transcription and communication of ideas and led in turn, almost directly, to the development of the various disciplines of philosophy which were so exemplary of the classical period in and around the Mediterranean starting in the first half of the first millennium BCE – most notably first with the epic poets Hesiod and Homer and then in turn with the Pre-Socratics who at least at some level started to use writing to expound and teach their ideas, and then of course culminating in the Classical Greek philosophical schools started by Plato and Aristotle – all of which ran parallel to the creation of the Torah in Hebrew which mirrored this same intellectual development but reflected the Hebrew rather than Hellenic belief systems.

Contrast today’s, or even Ancient Greek or Latin, alphabet systems/languages with the first writing systems that mankind developed – for example cuneiform (circa 4th millennium BCE) which was the form of writing used by the ancient Sumer-Babylon peoples, or the somewhat later (circa 3rd millennium BCE) Egyptian hieroglyphs, both systems of writing which were not (at least initially) alphabets or phonetic based, but were “idea” or “picture” based writing systems – consisting of what linguists call logograms, aka ideograms or pictograms, where each character or symbol represented a specific “concept” or “idea” rather than a specific sound which underpinned a specific word in a specific (spoken) language. Expounders of religion, theology or philosophy, or even history, that lived prior to the invention of alphabets, or prior to the invention of writing itself for that matter, did not have the luxury of being able to communicate sophisticated ideas outside of oral traditions, mouth to mouth so to speak. It was these ancient oral traditions which had been passed down for generations that began to be codified and documented in the Mediterranean when writing systems, and in particular alphabetic writing systems, were developed – hence the explosion of theological and philosophical texts that are so representative of this era, and this geographical area, of antiquity.

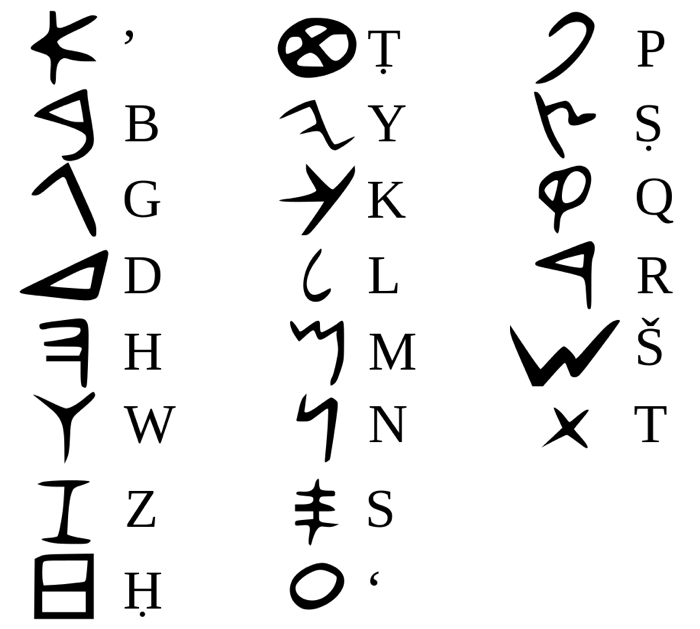

It is important to understand and recognize the significance of the fact that writing systems, more specifically alphabetic writing system are the means by which spoken words in a particular language can be represented, as opposed to symbolic or ideological representations of meaning which were codified in the older, more archaic forms of writing like Egyptian hieroglyphs for example. The invention of the alphabetic system that is widely adopted throughout the Mediterranean at this time is attributed to the Phoenicians, i.e. the “Phoenician alphabet” which is the parent system of not only the ancient Greek alphabet, but also the Hebrew alphabet, the latter of which was used to codify and document Biblical Hebrew, a Canaanite Semitic language spoken by the ancient Israelites, i.e. the language that was spoken by the authors of the Torah[1]. The words of these ancient writing systems, as they are today in all Western European languages, are phonetic correspondents to the spoken word, i.e. the letters are grouped into words to capture specific sounds, i.e. words, and in turn these words are compiled into sentences which not only reflect the spoken words themselves, but also together convey a specific meaning.

Figure 4: Ancient Phoenician alphabet characters[2]

Figure 4: Ancient Phoenician alphabet characters[2]

While this may seem like an obvious fact, this is a very important characteristic of the written word as it developed in antiquity and has specific implications in particular when trying to reconstruct not just the sounds and pronunciations of words that are represented in ancient writing systems, but also how these words and sentences (and some of the ancient scripts did not have punctuation to even delineate sentences even after alphabetic writing systems were introduced) are to be understood and in turn “translated”.

When trying to understand the meaning of a particular word or phrase in an ancient writing system for example, when trying to “translate” the word, or perhaps more accurately “transliterate” the term, especially when a word or phrase is representative of a language that may no longer be in use at all today (i.e. is “dead” in linguistic terms), it is sometimes impossible to not only know how the word was spoken or pronounced, but in some cases (in particular when dealing with writing systems from before the turn of the first millennium BCE), but also sometimes not possible to truly understand the “meaning” of the word or phrase that the ancient author is trying to convey. In many cases however, while it is not possible to know exactly how some ancient dialects and languages “sounded”, or how some ancient words we find in ancient texts were actually “pronounced”, we can still at some level at least come to understand the meaning of a word written in ancient language representing a spoken dialect that is “dead”. This issue is very relevant for example in the field of linguistics where word pronunciation rather than word spelling or writing is the dominant factor in trying to determine the origins and/or descendants of specific languages and categorizing language families in general.

For example, in these ancient myths which are transcribed by various scribes in various languages in various different writing systems, the names of gods and deities and their naturalistic counterparts which they represented (such as Air, Water, Earth, Fire, Sky, or Heaven for example which are in turn the first archaic principles which manifest in the material universe in almost all creation mythology) were looked upon as relatively synonymous concepts or ideas, almost interchangeable in fact, to the ancient author given the belief system and language (spoken and written) within which he was conveying his ideas. Whereas to the modern day translator who is utilizing a language system which presumes that the natural principles and the deities which were representative of them are two different concepts entirely. Hence a marked and unique difficulty in translating these ancient tongues as well as perhaps the reason why the belief systems of these ancient peoples are sometimes, in fact often times, misconstrued as “polytheistic” This becomes an especially significant problem that is many times overlooked, or at the very least underemphasized, by modern scholars who we rely on to for modern translations of ancient texts into various modern languages which are presented to the modern reader as accurate “translations”. This is especially true when trying to translate the ancient mythology; like the language in Genesis, Hesiod’s Theogony, or even more so in the Sumer-Babylonian Enûma Eliš for example, all of which represent some of the very oldest prose extant from ancient civilizations.

While ancient Hebrew does not necessarily fall under this group or heading of languages whose sounds or meanings have not survived given its continuous use by rabbinic scholars and the Jewish community into modern times, that does not necessarily mean that all translations of the Biblical Hebrew we find in the Hebrew Bible into modern languages accurately reflects the true meaning or symbolism that the words may have had in antiquity, in either their written or spoken form. It is important to recognize that these mythological and historical narratives which represent some of the oldest written historical texts we have from early and pre-civilized mankind were written down in antiquity so that they could be faithfully transmitted and distributed, so that they were preserved as it were, and were meant to complement rather than replace the surrounding oral and teaching tradition. A tradition which was marked by a direct transmission of “knowledge” from a competent and learned teacher to competent and properly trained student, representing a base of “knowledge” that reaches much further back in antiquity than we have written records for. The Torah is no exception to this hence the scholarly disputes on the date of the Old Testament texts.

Furthermore, while a spoken language and its writing system are closely related, they are not necessarily equivalent, i.e. there is not a one to one relationship between a spoken language and a written language in antiquity as there is today. This is not just a happenstance characteristic attribute of ancient writing systems, but in fact a fundamental characteristic, and arguably the underlying purpose and intent of their invention. In other words, writing systems in antiquity, and in particular alphabetic writing systems like Hebrew and Greek, were perhaps developed specifically to solve this very problem, i.e. to represent different spoken languages in a single script or writing system that could be easily learned by different scribes from different tribes or peoples such that a socio-cultural mythological tradition could be accurately preserved not only in content but also in spoken form. The spoken word in antiquity was looked upon with much greater reverence than it is today and this must also be kept in mind when trying to interpret the meaning of these ancient texts. This is how these textual traditions came to be understood as “divinely inspired”, or in later terms as “the word of God” as we find in not just the Judeo-Christian textual tradition but also in the Vedic tradition as well as the Muslim tradition surrounding the Qurʾān.

Cuneiform for example was used to express many different languages in the ancient Sumer-Babylonian region of the Near East for example – Akkadian and Old Babylonian among others. Perhaps the best known illustration, and ultimate power, of this concept is the well renowned Rosetta Stone inscriptions from ancient Egypt which captures the same passage, i.e. the same groups of “spoken” words or “language”, in three different ancient writing systems – Demotic (a form of Egyptian script), ancient Greek, and hieroglyphics. The Rosetta Stone of course was a critical instrument to helping modern scholars and linguists translate to and from these ancient writing systems into modern languages. In other words, a language can, and was in many cases in antiquity, represented by different writing systems and while this was a common practice in antiquity, it is rarely done if at all in modern times. The English language is expressed in the Roman/Latin alphabet today and no one would ever think to express it in a different form of writing, in say Arabic for example. The situation in antiquity was markedly different however, and this needs to be taken into account whenever dealing with ancient textual translations.

It’s also worth noting that oral communication in and of itself does not distinguish mankind from the rest of the life on the planet. For example whales or apes can communicate with each other orally and have even been shown to have different “dialects” that vary between geographic regions and specific names, or sounds, for individuals. In many respects, what distinguishes mankind from the rest of the species on Earth is writing, a development which supports the systematic construction of ideas and concepts that in turn allowed mankind to flourish, and ultimately dominate, life on Earth.

Prior to the development of writing however, for tens of thousands of years at least, mankind (Homo sapiens) leveraged the same tools as many of the other species on the planet for communication, namely oral communication and the creation of sound vibrations to communicate ideas between individuals. Hence the sacred perspective mankind had on almost all ancient language and forms of writing – the Sanskrit of the Indo-Aryans, the Hebrew of the Jews, and even the hieroglyphs of the Egyptians, they all believed that language and writing itself was wrapped up in and fundamentally related to the divine, as they perceived the whole world.

This is also why virtually all of the ancient philosophical schools regard the transmission of oral teachings as just as important, if not more important, that then written doctrines for true “understanding”. This holds true not just for the Vedic tradition, which has an unbroken oral transmission tradition that lasts to this day, but also with the Jewish tradition as well which from an orthodox standpoint rests true understanding of the faith upon the “Oral Torah” (Hebrew: תורה שבעל פה, or Torah she-be-`al peh, literally translated as the “Torah that is spoken”) just as much as the written Torah, or Torah proper. The Oral Torah, or Oral Law as it is sometimes called, consists primarily of the Mishnam, compiled in the second century CE, as well as the Gemara, a series of commentaries on the Mishnam and Torah writings in general compiled in the 5th century CE, which together form what is known as the Talmud, talmud in Hebrew meaning literally “instruction” or “learning” stemming from the verb to “teach” or “study”.[3]

We also see very clear evidence for the existence, and importance, of true understanding, if we may call it that, to Plato and its relationship to his theory of forms in a few notable passages in Phaedrus.

Socrates: Writing, Phaedrus, has this strange quality, and is very like painting; for the creatures of painting stand like living beings, but if one asks them a question, they preserve a solemn silence. And so it is with written words; you might think they spoke as if they had intelligence, but if you question them, wishing to know about their sayings, they always say only one and the same thing. And every word, when once it is written, is bandied about, alike among those who understand and those who have no interest in it, and it knows not to whom to speak or not to speak; when ill-treated or unjustly reviled it always needs its father to help it; for it has no power to protect or help itself.

…

Socrates: Now tell me; is there not another kind of speech, or word, which shows itself to be the legitimate brother of this bastard one, both in the manner of its begetting and in its better and more powerful nature?

Phaedrus: What is this word and how is it begotten, as you say?

Socrates: The word which is written with intelligence in the mind of the learner, which is able to defend itself and knows to whom it should speak, and before whom to be silent.

Phaedrus: You mean the living and breathing word of him who knows, of which the written word may justly be called the image.[4]

Here Plato is clearly pointing out the limitations of writing, the very tool that has come into such widespread use by the time he is teaching, and a tool in fact that was not used at all by his teacher, Socrates. Here he establishes the supremacy of knowledge over “book learning” so to speak, knowledge which can be gained only by true understanding, what he refers to quite eloquently as the word written in the mind.

The tradition of Plato’s teachings in general in fact were surrounded by this notion of unwritten teachings[5], speaking to the existence of teachings which he never wrote down and which he presumably taught only to his closest and most direct pupils or disciples as it were. We know of the existence of these unwritten teachings from a variety of sources in antiquity, but perhaps the most intriguing is from the Seventh Letter, a letter in all likelihood written by Plato himself to a friend defending himself with respect to his involvement and ultimate responsibility for the beliefs and expositions of one of his former pupils, Dionysios, who had become embroiled in a political dispute in Syracuse.

Thus much at least, I can say about all writers, past or future, who say they know the things to which I devote myself, whether by hearing the teaching of me or of others, or by their own discoveries-that according to my view it is not possible for them to have any real skill in the matter. There neither is nor ever will be a treatise of mine on the subject. For it does not admit of exposition like other branches of knowledge; but after much converse about the matter itself and a life lived together, suddenly a light, as it were, is kindled in one soul by a flame that leaps to it from another, and thereafter sustains itself. Yet this much I know-that if the things were written or put into words, it would be done best by me, and that, if they were written badly, I should be the person most pained. Again, if they had appeared to me to admit adequately of writing and exposition, what task in life could I have performed nobler than this, to write what is of great service to mankind and to bring the nature of things into the light for all to see? But I do not think it a good thing for men that there should be a disquisition, as it is called, on this topic-except for some few, who are able with a little teaching to find it out for themselves. As for the rest, it would fill some of them quite illogically with a mistaken feeling of contempt, and others with lofty and vain-glorious expectations, as though they had learnt something high and mighty.[6]

Here Plato explains, that he did not commit these type of teachings to writing by design, as true understanding, or knowledge, of his teaching as he puts it, can only be transmitted from one person to another after much learning and life experience, this “kindling of fire from one soul to another” as he puts it, cannot be gained by any sort of textual transmission which is indirect, but only passed from “one soul to another” after much thought and consideration and much experience of “living the teaching” so to speak before true understanding, knowledge, can be awakened as it were. The message here is certainly consistent with that we find in the relevant passage from Phaedrus.

We also see references made to these unwritten teachings by Aristotle (Physics and Metaphysics, see Physics, 209b13–15), and also indirectly by Aristotle’s student Aristoxenus who in his treatise on harmonics (Elementa harmonica II 30-31) calls out Plato’s public “Lecture on the Good” as a failure mainly due to its esoteric and abstruse content on the mathematical and numerological underpinnings of first principles. i.e. the Good and the Same, teachings which do not find, at least directly, spoken to in his dialogues.[7]

[1] See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Biblical Hebrew’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 19 August 2016, 06:33 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Biblical_Hebrew&oldid=735203916> [accessed 24 August 2016].

[2] Source: Wikipedia contributors, ‘Phoenician alphabet’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2 September 2016, 22:17 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Phoenician_alphabet&oldid=737455990> [accessed 30 September 2016]

[3] See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Talmud’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 18 August 2016, 06:33 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Talmud&oldid=735032742> [accessed 24 August 2016] and Wikipedia contributors, ‘Oral Torah’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 11 July 2016, 14:15 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Oral_Torah&oldid=729334359> [accessed 24 August 2016]

[4] Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9 translated by Harold N. Fowler. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925. Phaedrus. Phaedrus 275a – 276b. From http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0174%3Atext%3DPhaedrus%3Asection%3D276b.

[5]Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 19 August 2016, 16:46 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plato%27s_unwritten_doctrines&oldid=735270414> [accessed 24 August 2016].

[6]Seventh Letter by Plato. Translated by J. Harward. From http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/seventh_letter.html. While the actual authenticity of the letter by Plato is debated by scholars it does for the most part reflect the writing style and philosophy as presented by Plato from the author’s perspective and so while perhaps not written by Plato’s hand, still nonetheless seems to accurately represent something akin to what Plato would write, specifically with respect to the specific part of the work cited herein.

[7] In the beginning of Aristotle’s student Aristoxenus’s treatise on harmonics, he explains to the reader that Plato’s public lecture ‘On the Good’ was not well received due to the lack of clarity within the context within which it was presented. That is to say the topic heading, i.e. ‘The Good’ was misleading to the audience because they were expecting a lecture on the all things that were “good” and “admirable”, practical advice on how to lead a good life perhaps, and what they got was a lecture on first principles and the mathematical (and numerological) basis for the preeminent existence of the Good as an ontological first principle, a direct reference to Plato’s unwritten teachings. Whether or not Plato’s public lecture ‘On the Good’ actually took place is the subject of debate and a good overview of the arguments on either side can be found in “Plato’s Lecture ‘On the Good’”, by Konrad Gaiser. Published by Brill in Phronesis, Vol. 25. No 1 (1980) pp 5-37]. Also see Wikipedia contributors, ‘Plato’s unwritten doctrines’ at Wikipedia contributors, ‘Plato’s unwritten doctrines’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 19 August 2016, 16:46 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plato%27s_unwritten_doctrines&oldid=735270414> [accessed 25 August 2016].

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!